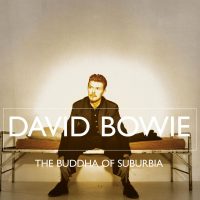

Recorded: June-September 1993

Recorded: June-September 1993

Producers: David Bowie, David Richards

Released: 8 November 1993

Personnel

David Bowie: vocals, guitar, keyboards, synthesizer, saxophone

Erdal Kızılçay: keyboards, synthesizer, trumpet, guitar, bass guitar, drums, percussion

Mike Garson: piano

Lenny Kravitz, Rob Clydessdale: guitar

Paul Davidson: bass guitar

Danny ‘Isaac’ Prevost: drums

Tracklisting

- ‘Buddha Of Suburbia’

- ‘Sex And The Church’

- ‘South Horizon’

- ‘The Mysteries’

- ‘Bleed Like A Craze, Dad’

- ‘Strangers When We Meet’

- ‘Dead Against It’

- ‘Untitled No. 1’

- ‘Ian Fish, UK Heir’

- ‘Buddha Of Suburbia’

Perhaps David Bowie’s most overlooked album, The Buddha Of Suburbia was initially marketed as the ‘Original Soundtrack Album’ for the four-part BBC television series of the same name. It was not, however, a soundtrack, and instead contained new recordings inspired by Bowie’s work on the programme.

The album itself only got one review, a good one as it happens, and is virtually non-existent as far as my catalogue goes – it was designated a soundtrack and got zilch in the way of marketing money. A real shame.

ContactMusic, 23 September 2003

The album was named after Hanif Kureishi bestselling novel, published in 1990. The book’s protagonist, Karim, was a Briton of Asian descent living in Bromley, Greater London, in the 1970s.

Music is integral to the semi-autobiographical work, which portrays a young mixed-race man’s struggles with racism, sexual experimentation, shifting fashions and trends, and class barriers. Kureishi, like Bowie, was brought up in Bromley and attended Bromley Tech, although Bowie was seven years his senior.

The BBC adapted Kureishi’s bildungsroman for television in 1993. That year Bowie took part in a Q&A with the author for Interview magazine. Published in the wake of Black Tie White Noise’s release in 1993, the interview touched upon Bowie’s upbringing, his early longing for fame, as well as fashion, sexuality, drugs, and relationships.

In February 1993 I was, fortuitously, invited by an American magazine to interview David Bowie. He’d attended, ten years previously, the school I’d gone to, though he had got out long before us, leading the way so that others, like Charlie Hero, could follow. ‘I knew at thirteen,’ he said to me, ‘that I wanted to be the English Elvis.’ Throughout the 70s he’d extended English pop music: he’d established ‘glam rock’, worn dresses and make-up, claimed to be gay, and written clever, knowing songs. He’d introduced people like Lou Reed and Iggy Pop to British audiences and written songs about Andy Warhol and Dylan. His influence on punk was crucial. And he’d made, with Brian Eno, experimental music – Low, “Heroes”, Lodger – which had lasted, which you could listen to today.He wasn’t merely rich or successful either. I could see he had movie-star glamour, that unbuyable, untouchable sheen which fame, style and a certain self-consciousness bestow on few people. He was, as well, extremely lively and curious, very enthusiastic about movies and books, and in particular, painting and drawing. [At school we’d had the same art teacher, Peter Frampton’s father.] Bowie was a man constantly bursting with ideas for musicals, movies, records; he appeared creative all day, drawing, writing on cards, playing music, ringing to ask what you thought of this or that, traveling, meeting people.

hanifkureishi.com

At the end of their encounter, Kureishi asked Bowie if two songs from Hunky Dory – ‘Changes’ and ‘Fill Your Heart’ – might be included in the TV show soundtrack. Bowie agreed and, emboldened, Kureishi chanced a further request.

As we left the restaurant and his black chauffeur-driven car sat there, engine running, I asked if he might fancy writing some original material too. He said yes and asked for the tapes to be sent to him.

hanifkureishi.com

Among the list of words Bowie associated with the album is “Pink Floyd”. If you listen to “Bleed Like a Craze Dad” There is a four note guitar lick that is reminiscent of the four note lick that lays the foundation for Pink Floyd’s “Shine on you Crazy Diamond” from the “Wish You Were Here” album. In fact if you take notes 1-2-3-4 from the Floyd song and play them in the order 3-4-1-2, you get the Bowie lick. Wondering if anyone else noticed?

Now that you mention it, I do hear it! (I’d never noticed it even though I am a longtime Floyd fan, so that’s a good catch.) I find it hard to imagine that was accidental.