The 22 January 1972 issue of the Melody Maker carried a groundbreaking interview with David Bowie, in which the singer admitted he was “gay, and always have been.”

The interview was conducted by reporter Michael Watts, and also introduced the Ziggy Stardust persona to the UK public.

David’s present image is to come on like a swishy queen, a gorgeously effeminate boy. He’s as camp as a row of tents, with his limp hand and trolling vocabulary. “I’m gay,” he says, “and always have been, even when I was David Jones.” But there’s a sly jollity about how he says it, a secret smile at the corners of his mouth. He knows that in these times it’s permissible to act like a male tart, and that to shock and outrage, which pop has always striven to do throughout its history, is a ball-breaking process. And if he’s not an outrage, he is, at the least, an amusement. “Why aren’t you wearing your girl’s dress today?” I said to him (he has no monopoly on tongue-in-cheek humour). “Oh dear,” he replied, “You must understand that it’s not a woman’s. It’s a man’s dress.”

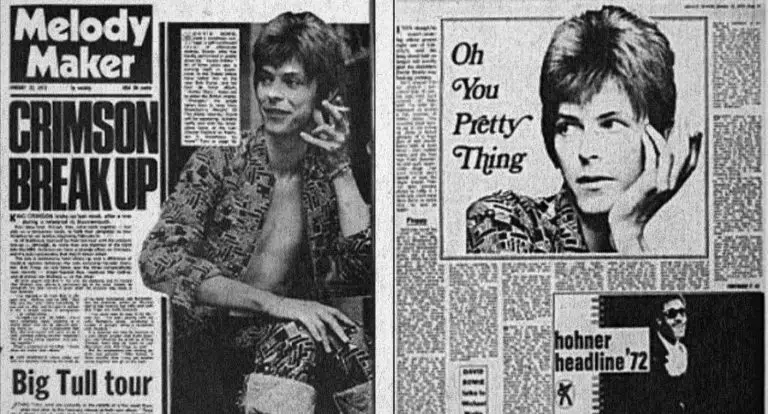

The interview was published under the headline “Oh! You Pretty Thing”. Bowie’s manager Tony Defries had wanted the announcement to be the UK weekly’s lead story, and was furious to learn that the break-up of King Crimson grabbed the main headline. A photograph of Bowie in full Ziggy regalia was printed on the front page, however.

As Melody Maker’s news editor at the time, I was a party to the decision to stick him on the front page. We were all pretty broad-minded on Melody Maker so the gayness didn’t put us off him. I don’t recall any adverse reaction from anyone.

David Bowie, Marc Spitz

Although the music weeklies enjoyed healthy circulations in the early 1970s, Bowie’s declaration did not garner the response his manager had hoped for. Although significant and symbolic, the singer later expressed gratitude that the revelation did not become a defining factor of his public image.

I found I was able to get a lot of tension off my shoulders by almost ‘outing’ myself in the press in that way, in very early circumstances. So I wasn’t going to get people crawling out the woodwork saying [seedy, muck-raking voice]: “I’ll tell you something about David Bowie that you don’t know…’ I wasn’t going to have any of that. I knew that at some point I was going to have to say something about my life. And, again, Ziggy enabled me to make things more comfortable for myself. There was an excitement that the age of exploration was really finally here. Which is what I was going through. It perfectly mirrored my lifestyle at the time. It was exactly what was happening to me. There was nothing that I wasn’t willing to try, to explore and see if it was really part of my psyche or my nature. I was terribly exploratory in every way, not just culturally but sexually and…God, there was nothing I would leave alone. Like a – it’s a terrible pun, but – like a dog with a bone, I suppose! So I buried it!The quote has taken on far more in retrospect than actually it was at the time. I’m quite proud that I did it. On the other hand I didn’t want to carry a banner for any group of people, and I was as worried about that as the aftermath. Being approached by organisations. I didn’t want that. I didn’t feel like part of a group. I didn’t like that aspect of it: this is going to start overshadowing my writing and everything else that I do. But there you go.

Mojo, July 2002

Although Bowie was not yet a household name, the story was picked up by the Evening Standard newspaper, which republished the “I’m gay” quotation. Bowie’s former manager Kenneth Pitt was not impressed: “I wasn’t at all happy when the ‘I’m Gay interview appeared’,” he said. “It wasn’t the kind of thing I would have advised him to do.”

In 2006 Michael Watts spoke of his memories of interviewing Bowie.

Two confessions, mine first, as the author of the interview that broke the news: the original article now reads horribly coy.I met Bowie in his publisher’s office, high above Regent Street. He was dolled up as Ziggy, before the world knew of rock stars from outer space. Skintight pantsuit, big hair, huge, red plastic boots – dazzling. Only recently had he stopped wearing a dress – ‘a man’s dress,’ he elaborated. He was charming, slightly flirtatious, but made me uncomfortable with myself. ‘Camp as a row of tents,’ I wrote – did I invent that phrase? – when I wanted to be unmanly and shout: he is unreservedly fabulous.

Soon he was coming out to me. ‘I’m gay,’ he said, ‘and always have been, even when I was David Jones.’ This sounds now like Daffyd in Little Britain, but it wasn’t comical then. In truth, I felt lucky. He’d almost spilled the beans to Jeremy magazine three years before. Did his admission matter? Well, laws on homosexuality had been reformed only five years previously. After Bowie came le deluge. He had shrewdly calculated the consequences, however. Busting taboos stokes the star-maker machinery. He was also just being honest. Sometimes, even in pop, honesty pays.

The Observer, 22 January 2006

Here’s the full Melody Maker article:

Oh, You Pretty ThingDAVID BOWIE, rock’s swishiest outrage; a self-confessed lover of effeminate clothes, Bowie, who has hardly performed in public since his ‘Space Oddity’ hit of three years ago, is coming back in super-style. In the States, critics have hailed him as the new Bob Dylan, and his tour de force album Hunky Dory looks set to enter the British charts. ‘Changes’, the single taken from it, was Tony Blackburn’s Record of the Week recently. David will be appearing, suitably spiffy and with his three-piece band, at the Lanchester Festival on February 3. Breathless for more? Turn to page 19…

Even though he wasn’t wearing silken gowns right out of Liberty’s, and his long blond hair no longer fell wavily past his shoulders David Bowie was looking yummy. He’d slipped into an elegant – patterned type of combat suit, very tight around the legs, with the shirt unbuttoned to reveal a full expanse of white torso. The trousers were turned up at the calves to allow a better glimpse of a huge pair of red plastic shoes; and the hair was Vidal Sassooned into such impeccable shape that one held one’s breath in case the slight breeze from the open window dared to ruffle it. I wish you could have been there to varda him; he was so super.

David uses words like “varda” and “super” quite a lot. He’s gay, he says. Mmmmmmmm. A few months back, when he played Hampstedt’s Country Club, a small greasy club in north London which has seen all sorts of exciting occasions, about half the gay population of the city turned up to see him in his massive floppy velvet hat, which he twirled around at the end of each number. According to Stuart Lyon, the club’s manager, a little gay brother sat right up close to the stage throughout the whole evening, absolutely spellbound with admiration. As it happens, David doesn’t have much time for Gay Liberation, however. That’s a particular movement he doesn’t want to lead. He despises all these tribal qualifications. Flower Power he enjoyed, but it’s individuality that he’s really trying to preserve. The paradox is that he still has what he describes as “a good relationship” with his wife. And his baby son, Zowie. He supposes he’s what people call bisexual.

They call David a lot of things. In the states he’s been referred to as the English Bob Dylan and an avant garde outrage, all rolled up together. The New York Times talks of his “coherent and brilliant vision.” They like him a lot there. Back home in the very stiff upper lip UK, where people are outraged by Alice Cooper even, there ain’t too many who have picked up on him. His last but one album The Man Who Sold The World, cleared 50,000 copies in the States; here it sold about five copies, and Bowie bought them. Yes, but before this year is out all those of you who puked up on Alice are going to be focusing your passions on Mr. Bowie, and those who know where it’s at will be thrilling to a voice that seemingly undergoes brilliant metamorphosis from song to song, a songwriting ability that will enslave the heart, and a sense of theatrics that will make the ablest thespians gnaw on their sticks of eyeliner in envy. All this and an amazingly accomplished band, featuring super-lead guitarist Mick Ronson, that can smack you round the skull with their heaviness and soothe the savage breasts with their delicacy. Oh, to be young again.

The reason is Bowie’s new album “Hunky Dory,” which combines a gift for irresistible melody lines with lyrics that work on several levels – as straight forward narrative, philosophy or allegory, depending how deep you wish to plumb the depths. He has a knack of suffusing strong, simple pop melodies with words and arrangements full of mystery and darkling hints. Thus ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’, the Peter Noone hit, is one strata, particularly the chorus, about the feelings of a father-to-be; on a deeper level it concerns Bowie’s belief in a superhuman race – homo superior – to which he refers obliquely: “I think about a world to come/where the books were found by The Golden Ones/Written in pain, written in awe/by a puzzled man who questioned what we were here for/Oh, The Strangers came today, and it looks though they’re here to stay.” The idea of Peter Noone singing such a heavy number fills me with considerable amusement. That’s truly outrageous, as David says himself.

But then Bowie has an instinct for incongruities. On The Man album there’s a bit at the end of ‘Black Country Rock’ where he superbly parodies his friend Marc Bolan’s vibrato warblings. On Hunky Dory he devotes a track called ‘Queen Bitch’ to the Velvets wherein he takes off to a tee the Lou Reed vocal and arrangement, as well as parodying, with a storyline about the singer’s boyfriend being seduced by another queen, the whole Velvet Underground genre. Then again, at various times on his albums he resorts to a very broad Cockney accent, as on ‘Saviour Machine’ (The Man) and here with (‘The Bewley Brothers’. He says he copped it off Tony Newley. because he was mad about ‘Stop The World’ and ‘Gurney Slade’: “He used to make his points with this broad Cockney accent and I decided that I’d use that now and again to drive a point home.”

The fact that Bowie has an acute ear for parody doubtless stems from an innate sense of theatre, He says he’s more an actor and entertainer than musician; that he may in fact, only be an actor and nothing else: “Inside this invincible frame there might be an invisible man.” You kidding? “Not at all. I’m not particularly taken with life. I’d probably be very good as just an astral spirit.” Bowie is talking in an office at Gem Music, from where his management operates. A tape machine is playing his next album, The Rise And Fall of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, which is about this fictitious pop group. The music has got a very hard edged sound, like The Man Who Sold The World. They’re releasing it shortly, even though Hunky Dory has only just come out.

Everyone just knows that David is going to be a lollapalooza of a superstar throughout the entire world this year, David more than most. His songs are always ten years ahead of their time, he says, but this year he has anticipated the trends: “I’m going to be huge, and it’s quite frightening in a way.” he says, his big red boots stabbing the air in time to the music. “Because I know that when I reach my peak and it’s time for me to be brought down it will be with a bump.” The man who’s sold the world this prediction has had a winner before of course. Remember ‘Space Oddity’, which chronicled Major Tom’s dilemma, aside from boosting the sales of the stylophone? That was a top ten hit in 1968, but since then Bowie has hardly performed at all in public. He appeared for a while at an arts lab, he co-founded in Beckenham, Kent, where he lives, but when he realised that people were going there on a Friday night to see Bowie the hit singer working out, rather than for any idea of experimental art, he seems to have become disillusioned. That project foundered, and he wasn’t up to going out on one-nighters throughout the country at that particular time.

So in the past three years he has devoted his time to the production of three albums David Bowie (which contains ‘Space Oddity’) and The Man Who Sold The World for Philips, and Hunky Dory for RCA. His first album, Love You Till Tuesday, was released in 1968 on the new Deram label but it didn’t sell outstandingly, and Decca, it seems, lost interest in him. It all began for him, though, when he was 15 and his brother gave him a copy to play an instrument he took up sax because that was the main instrument featured in the book (Gerry Mulligan, right?) So in 1963 he was playing tenor in a London R and B band before going on t found a semi-pro progressive blues group, called David Jones and The Lower Third (later changing his name in 1966 when Davy Jones of The Monkees became famous). He left this band in 1967 and became a performer in the folk clubs.

Since he was 14, however, he had been interested in Buddhism and Tibet, and after the failure of his first LP he dropped out of music completely and devoted his time to the Tibet Society, whose aim was to help the lamas driven out of that country in the Tibetan/Chinese war. He was instrumental in setting up the Scottish monastery in Dumfries in this period. He says, in fact, that he would have liked to have been a Tibetan monk, and would have done if he hadn’t met Lindsay Kemp, who ran a mime company in London: “It was as magical as Buddhism, and I completely sold out and became a city creature. I suppose that’s when my interest in image really blossomed.”

David’s present image is to come on like a swishy queen, a gorgeously effeminate boy. He’s as camp as a row of tents, with his limp hand and trolling vocabulary. “I’m gay”, he says, “and always have been, even when I was David Jones.” But there’s a sly jollity about how he says it, a secret smile at the corners of his mouth. He knows that in these times it’s permissible to act like a male tart, and that to shock and outrage, which pop has always striven to do throughout its history, is a balls-breaking process.

And if he’s not an outrage, he is, at the least, an amusement. The expression of his sexual ambivalence establishes a fascinating game: is he, or isn’t he? In a period of conflicting sexual identity he shrewdly exploits the confusion surrounding the male and female roles. “Why aren’t you wearing your girl’s dress today?” I said to him (he has no monopoly on tongue-in-cheek humour). “Oh dear,” he replied, “You must understand that it’s not a woman’s. It’s a man’s dress.”

He began wearing dresses, of whatever gender, two years ago, but he says he had done outrageous things before that were just not accepted by society. It’s just so happened, he remarks, that in the past two years people have loosened up to the fact that there are bisexuals in the world – “and – horrible fact – homosexuals.” He smiles, enjoying his piece of addenda. “The important fact is that I don’t have to drag up. I want to go on like this for long after the fashion has finished. I’m just a cosmic yob, I suppose. I’ve always worn my own style of clothes. I design them. I designed this.” He broke off to indicate with his arm what he was wearing. “I just don’t like the clothes that you buy in shops. I don’t wear dresses all the time, either. I change every day. I’m not outrageous. I’m David Bowie.”

How does dear Alice go down with him, I asked, and he shook his head disdainfully: “Not at all. I bought his first album, but it didn’t excite me or shock me. I think he’s trying to be outrageous. You can see him, poor dear, with his red eyes sticking out and his temples straining. He tries so hard. That bit he does with the boa constrictor, a friend of mine, Rudy Valentino, was doing ages before. The next thing I see is Miss C. With her boa. I find him very demeaning. It’s very premeditated, but quite fitting with our era. He’s probably more successful then I am at present, but I’ve invented a new category of artist, with my chiffon and raff. They call it pantomime rock in the States.”

Despite his flouncing, however, it would be sadly amiss to think of David merely as a kind of glorious drag act. An image, once strained and stretched unnaturally, will ultimately diminish an artist. And Bowie is just that. He foresees this potential dilemma, too, when he says he doesn’t want to emphasise his external self much more. He has enough image. This year he is devoting most of his time to stage work and records. As he says, that’s what counts at the death. He will stand or fall on his music. As a songwriter he doesn’t strike me as an intellectual, as he does some. Rather, his ability to express a theme from all aspects seems intuitive. His songs are less carefully structured thoughts than the outpourings of the unconscious. He says he rarely tries to communicate to himself, to think an idea out.

“If I see a star and it’s red I wouldn’t try to say why it’s red. I would think how shall I best describe to X that that star is such a colour. I don’t question much; I just relate. I see my answers in other people’s writings. My own work can be compared to talking to a psychoanalyst. My act is my couch.” It’s because his music is rooted in this lack of consciousness that he admires Syd Barrett so much. He believes that Syd’s freewheeling approach to lyrics opened the gates for him; both of them, he thinks, are the creation of their own songs. And if Barrett made that initial breakthrough, it’s Lou Reed and Iggy Pop who have since kept him going and helped him to expand his unconsciousness. He and Lou and Iggy, he says, are going to take over the whole world. They’re the songwriters he admires.

His other great inspiration is mythology. He has a great need to believe in the legends of the past, particularly those of Atlantis; and for the same need he has crafted a myth of the future, a belief in an imminent race of supermen called homo superior. It’s his only glimpse of hope, he says – “all the things that we can’t do they will.” It’s belief created out of resignation with the way society in general has moved. He’s not very hopeful about the future of the world. A year ago he was saying that he gave mankind another 40 years.” A track on his next album, outlining his conviction, is called ‘Five Years’. He’s a fatalist, as you can see. ‘Pretty Things’, that breezy Herman song, links this fatalistic attitude with the glimmer of hope that he sees in a birth of his son, a sort of poetic equation of homo superior. “I think,” he says, “that we have created a child who will be so exposed to the media that he will be lost to his parents by the time he is 12.” That’s exactly the sort technological vision that Stanley Kubrik foresees for the near future in A Clockwork Orange. Strong stuff. And a long, long way away from camp carry-ons.

Don’t dismiss David Bowie as a serious musician just because he likes to put us all on a little.

Melody Maker, 22 January 1972

Also on this day...

- 1996: Live: Spektrum, Oslo

- 1973: Recording: Aladdin Sane

- 1972: Rehearsal: Theatre Royal, Stratford, London

- 1970: Live: Three Tuns, Beckenham

- 1969: Filming: Luv by Lyons Maid

- 1966: Live: David Bowie and the Lower Third, Marquee Club, London

Want more? Visit the David Bowie history section.